Why Millbrook? I'll tell you. #1) I live here; and #2) for such a little place it's got an outsized reputation and at least some of you will want to know more. So then, I'll begin:

First there was the Word, and the Word was "Quakers." OK, not precisely accurate. Gilded, low profile little Millbrook actually started, in a sense anyway, back in 1697 when nine real estate speculators, called patentees, obtained a heart-of-the-Hudson-Valley, plus-or-minus-100,000-acre land grant from the English crown. Logically enough, this Edenic parcel, which the European mind despised as "unproductive," came to be called the Great Nine Partners Patent. (There was also a Little Nine Partners Patent, but that's another story). The Quakers didn't come for several generations, but when they did, they came in numbers, escaping depressingly familiar religious intolerance on the part of former neighbors in New England and Long Island.

In today's Millbrook the probity and industry of those early Quakers is a dim memory - more correctly a "non-memory." Typical white-clapboarded New England quaintness is no memory at all. Millbrook is the product of three transformative 19th century forces: 1) the railroad; 2) post-Civil War private fortunes; and 3) America's Anglophilic fascination with, and determination to create, an indigenous culture of country estates.

Setting aside a handful of buildings predating the railroad, Millbrook dates entirely from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its roots as a farming community are shallow, having developed instead as a service center for a network of local estates. Among the many things I like about Millbrook - apart from the lack of a "strip" on the outskirts, the willingness of local merchants to run a tab, and a bank that actually keeps mortgages in lieu of bundling them off to souless investors - is the fact that big old houses were its primary raison d'etre.

For many years in my fiscally irresponsible past, I actually had a cook. Now I eat here.

The Quakers began trickling in by the 1740s, transforming the virginal forests into productive farms and Wappingers Creek into a water-powered industrial zone. In the process, they established two villages, Hart's and Mechanic, hamlets almost on top of one another. Since in those days everyone walked, I suppose they seemed further apart than they were. Hart's was home to a dozen 18th century mills. A compound of elegant Hart family houses still survives at the north end of Millbrook. In 1780 the Quakers of Hart's and Mechanic were sufficiently prosperous to built a fine brick meeting house, still extant, in the middle of Mechanic. In 1797, the local elders bought the Mechanic country store, seen below, formerly the property of one Samuel Mabbett who fled the country after unadvisedly backing the Brits during the revolution. Mabbett's store became the Nine Partners Academy, a famous 19th century co-educational boarding school, light years ahead of its time, that considered the education of girls and boys to be of equal importance.

Such was the world of Millbrook (before there was a Millbrook), from the arrival of the Quakers until the close of the Civil War.

Certain local Quakers didn't just prosper, they became outright rich. Notable among these was Jonathan Thorne (1801-1884) who, as a lad of 19, sought his fortune in New York. He died 65 years later at a house on Washington Square North, the largest leather manufacturer in America and a millionaire director of banks and coal companies. In 1849 Thorne inherited his father's rather grand (for a Quaker farmer) 2.5 story rural Federal cube. Called Thorndale and located on land obtained, interestingly, in lieu of a bad debt, it was almost exactly equidistant between Hart's and Mechanic. Thorndale was an early harbinger of architectural efforts to come. Thorne himself, by virtue of the same arc of change, was too, shedding Quakerism and becoming an Episcopalian.

If Millbrook had a biological father - putting aside the Quaker century of Hart's and Mechanic - it was George Hunter Brown, president of the United States Condensing Company. In 1867 Brown built the future prototypical Millbrook estate, a remarkable looking structure designed by an actual architect, the obscure, if highly original, Edward Tuckerman Potter. Brown named the property Millbrook Farms. Why prototypical? Well to begin with, it had gates and gate lodges, hardly a feature of local Quaker farms. The main house was artistically sited at the end of a long and picturesque drive. Greenhouse complexes bulged with competition quality horticulture, and ancillary cottages housed professional staff. Millbrook Farms was indeed a farm, but its focus was less on profit than the demonstration of often expensive advances in scientific agriculture. Beside being a condensed milk magnate and sometime supervisor of the Town of Washington, Brown was also a railroad executive who engineered the northern extension of the Dutchess and Columbia County RR. Both Hart's and Mechanic felt entitled to host the new station. A Brown-sponsored compromise resulted in a site located between the two. The mandarins of the Dutchess and Columbia dubbed it Millbrook Station, an homage to Brown and his estate. Hart's and Mechanic, already in decline from the steady departure of industry and agriculture to new lands in the west, grew ever sleepier. Burgeoning unincorporated Millbrook Station, by contrast, thrived.

Besides the Thornes, other farmers were doing well, in particular the Hams. Conrad Frederick Ham arrived in Millbrook in 1740. By 1871 his grandson, Milton Conrad Ham, had prospered sufficiently to build this elaborate Italianate mansion amidst 350 acres of working fields. Lynfeld, as the place was called, was a different breed of cat from Millbrook Farms. It had neither gates nor showy greenhouses, long picturesque drives nor, for that matter, an architect. Ham's bachelor brother-in-law, John Jay Ferris, designed this appealing house whose stylistic naivete went unnoticed amidst the giddy architectural fancies of the day. As soon as it was finished, unlike Mr. Brown's architect, Ferris moved into it with his sister and her husband.

And then there was John D. Wing, another local Quaker who, like Jonathan Thorn, poured a portion of profits made elsewhere (in his case, the industrial production of soda ash) into a gentleman's seat at Millbrook. Wing had been a graduate of the famous Quaker Boarding school and, when the school went under in 1863, bought the building and mined it for architectural fabric used in the construction of Mapleshade. John Wing, as we shall see, was the "missing link" between farmers like Ham and hilltoppers like Brown.

Let me explain. Wing was pals with a hugely talented engineer named Henry J. Davison, whose scapegrace brother-in-law had been installed (or else!) on a healthful farm in the vicinity of Millbrook Station. The worldly Mr. Davison, by virtue of said brother-in-law, was familiar with the local countryside, but in the early 1880s, while mulling over where to build his own country place, he waffled over Millbrook. According to his son, interviewed many years later in the "Poughkeepsie Journal," Davison had no desire to own a grand estate in a neighborhood where his was the only one. Altamont got built because Davison convinced his friend John Wing, his brother-in-law Frederick Jones, and a fellow engineer named Charles F. Dieterich to build in Millbrook too. James E. Ware, a fashionable architect with a New York practice, designed all four of what we might call the "Davison gang" estates. The net result was imposition of a new paradigm on little Millbrook, and the age of the "hilltopper" was born.

Here's Wing's new house, Sandanona, designed with characteristic abandon by James E. Ware. Portions of Mapleshade, having originated as parts of the Quaker School, were now incorporated into Sandanona, notably a school bell whose melodious tolling recalled to Wing the golden days of his youth, or something.

The Wing estate checked all the boxes - gatehouse, aesthetic drives, big greenhouses, cottages, etc., etc. In 1888, the year after completing Sandanona, Wing had Ware design a second house on the property for his eldest son, Morgan. Called Shadow Lodge, it wouldn't be the last secondary mansion on a local estate, built for a family member.

By 1903 Edgewood belonged to Harry Harkness Flagler, son of Standard Oil partner and Florida real estate and railroad tycoon, Henry Morrison Flagler. The original Ware house for Frederick Jones is the section on the right; the left side of the building is a Flagler addition.

Ware designed Altamont in 1883, Edgewood in 1884, and Sandanona in 1886. It was his 1889 commission to design the Daheim estate for Charles F. Dieterich, president of the Union Carbide Corporation, that was arguably the greatest of his career. The job lasted almost 20 years, beginning with "temporary" additions to a pre-existing farmhouse seen below. Instead of being pulled down and replaced with something showier, the farmhouse kept growing, as my late mother would have said, like Topsy.

Dieterich bought 50 individual farms to create Daheim. Small-scale family farming in the region, as noted earlier, was on the wane and old farms were readily available at bargain prices. Dieterich and his groundskeeper Ludwig Gros divided Daheim's 2500 acres into a fenced deer park on the north, traversed by 12 miles of carriage roads, and a pair of greenhouse complexes, a model dairy farm and a mansion surrounded by fountains, tennis court and Swiss Chalet style bowling alley, on the south.

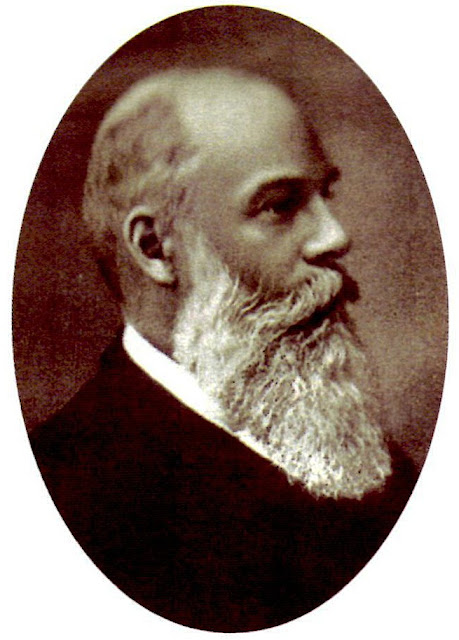

This is Oakleigh Thorne - actually, the first of 4 successive Oakleigh Thornes - who, upon his father's death in 1889, inherited Thorndale. Together with his horticulturist wife, the former Helen Stafford, Thorne beautified Thorndale until 1905, when architect A.J. Bodker turned what had basically been a Ham-ish farmhouse into something more appropriate to the new Millbrook.

George Brown went down in financial flames during the 1880s, after which Oakleigh Thorne's Uncle Samuel moved into Millbrook Farms and renamed it Thorncrest.

On New Year's Day, 1896, Millbrook was officially incorporated. High time, it would seem, as the village already possessed a library, a weekly paper called the "Round Table," two schools, four churches, a Masonic Lodge, an outpost of the WCTU, a bank with $50,000 in capital, a volunteer fire department, and 1100 residents surrounded by a necklace of upscale country properties that ornamented the surrounding hills. Donation of the Thorne Building (seen below), a combination school and performance space dedicated to the memory of Jonathan (who made the money) and his wife Lydia, precipitated the event. If you're going to donate something, there has to be someone or something (in this case, an incorporated village) to accept the donation. Incorporation had symbolic meaning as well, being the imprimatur of Millbrook's official identity.

While another generation of Hams worked the fields, a new group, organized officially in 1907 as the Millbrook Hunt, galloped across them in pursuit of the fox.

There was nothing effete about Millbrook's foxhunters. Take David Ulysses Sloan, seen below between hunt cronies Bryce Wing and Harvey Ladew. Millbrook Hunt master Oakleigh Thorne lured Sloan from a Paris job at Lazard Freres to a Millbrook life of hard hunting and expensive liquor. Sloan, a tough-guy socialite from Central Casting, spent most of his subsequent waking hours on horseback. He died of a heart attack at age 51, either cheering at a Harvard-Yale game or at home in bed, depending on the account you read. (Personally, I prefer the former). Sloan's house, interestingly, was in the village, and called Greyhouse.

The Millbrook Inn, a hilltopper favorite for surplus guests, visiting fox hunters, collateral relations and wintertime visits when their big houses were closed, made sense in the context of the village. Millbrook was not a tourist destination; if you weren't invited, there was nothing to do.

Henry Davison's son Harry ignored this basic fact when he sank his own and, as it turned out in court, much of his siblings' inherited money into Millbrook's greatest boondoggle, the Halcyon Hall Hotel. At least he didn't scrimp. Opened in 1893, the hotel was a hushed world of expensive curtains, Turkish rugs, antique furniture, masses of fresh flowers, permeated by a sort of fin-du-siecle Muzak provided by live alternating orchestras, one of which is seen in the second image below. According to some, Harry's hotel was evidence of a competitive obsession with the lordly Thornes - a good story, although not one with much evidence to back it up. The hotel went belly up in 1901. It remained vacant and lightly vandalized until Miss May Bennett arrived in 1907 and turned it into a women's college.

Such was Millbrook by the first decade of the 20th century. Next week: a trip to the present.

%2BBryce%2BWing%2C%2BDave%2BSloan%2C%2BHarvey%2BLadew%2C%2Bphoto%2Bcourtesy%2BMr.%2B%26%2BMrs.%2BTony%2BSloan.jpg)

Ahh...the Millbrook Diner over on Franklin Ave. I read a few of the reviews on Yelp. The tuna melt sounds good for lunch. I understand that these classic diners are an institution on the East Coast.

ReplyDeleteThis made for fun reading, John. Sandanona puts me in mind of the fictional haunted Hill House of Shirley Jackson's novel. Thorncrest, which you have covered before, sadly tops my list of vanished houses I'd most like to be able to visit. Looking forward to Part 2.

ReplyDeleteSide-saddle, and double reins! Beautifully groomed hunters, just look at those tidy hooves. And one dares to assume there's a proper mounting block just around the corner. Thank you, John, for sharing the stuff of dreams...when I was a young coed, the saddle girths didn't match, the horses were all gifts to the college with bad mouths and worse habits, and a short woman mounted a tall horse by lengthening the leathers and doing a circus act.

ReplyDeleteAnd I do like the looks of that diner. There's a decent Rueben sandwich in there, somewhere.