This house was controversial from the day it was built. In her diary at the time, Mrs Frances Glessner made a list of visitors' comments: "It is queer," said Mr. Lewis; "You have astonished everyone with your strange house," said Mrs. Jewett; "How do you get into it?" from many people; and from George Pullman, the sleeping car magnate who lived across the street, "I don't know what I have ever done to have that thing staring me in the face every time I go out of my door" - hopefully not said to Mrs. Glessner's face.

John J. Glessner (1843-1936) was a founder of Warder, Bushnell and Glessner, a manufacturer of farm machinery that apparently also printed money (I'm kidding, OK?) In 1870, the firm moved to Chicago, Glessner married Frances Macbeth (d. 1932), and by 1885, with a teenaged boy and an 8-year-old daughter in tow, he bought 3 lots on Chicago's fashionable South Prairie Avenue. After interviewing William Potter, Robert H, Robertson and Stanford White, all of whom are well know to readers of this column (and please don't correct me if they're not), Glessner hired the prominent and fashionable Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886), the only American architect I know of who's had an architectural style named after him, to wit: Richardsonian Romanesque. Business footnote: In 1902 Warder, Bushnell and Glessner joined with four other firms to become the International Harvester Corp., John Glessner, Vice President.

Below is a modern view of East 18th St. and South Indiana Avenue, half a block from the Glessner house. The area is now called the South Loop. The 3 Graces of residential Chicago in the last decades of the 19th century were South Prairie, South Indiana and South Calumet Avenues. Pleasant as the neighborhood is today, it was a wholly different place back then.

A line like, "The sunny street of the sifted few," used to describe Chicago's Prairie Avenue, might make us smile today, but truth be told it wasn't far off the mark. Chicago was rich and South Prairie, seen below in its heyday (that's Glessner, first house on the right), was its residential ne plus ultra - not just for cranky George Pullman, but Marshall Field, Frank Lowden, William Armour, and a host of promenenti none the less important for us not having heard of them today.

The fall of South Prairie and it's flanking attendants was precipitous and catastrophic. Almost immediately after 1900, industrial development unfettered by zoning pressed south from Chicago's too close downtown. Disloyal fashion promptly fled north to the new suburbs, while the Jazz Age children of Prairie Avenue dismissed their parents' gloomy Victorians as not worth saving. By 1905 a printing plant had invaded the neighborhood. By 1910 businesses and rooming house operators were the only buyers in what had become a rout. When zoning did arrive in 1923, South Prairie Avenue found itself zoned for industry and manufacturing. Demolition for tax purposes began in earnest in the '20s and, together with abandonment, became rampant by the '30s. When Mrs. Addie Hibbard Gregory left her home of 77 years at 1638 South Prairie Avenue in 1944, no one else was left.

In the wake of the zoning shock, and painfully aware of what had already happened to his neighbors, Glessner deeded his house to the Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, with the provision that he and his wife would live there until their deaths. So much for best laid plans. When Glessner followed his wife to the grave in 1936, the AIA decided it couldn't afford to keep the place. They gave it back to the family who, two years later, donated it to the Armour Institute of Technology. From the late 1930s until 1958, 1800 South Prairie Avenue was a research center. After that it became a printing plant for something called the Lithographic Technical Foundation. In 1966, the lithographers left and the house went on the market for $70,000. No one seemed interested and demolition loomed.

Men on white horses arrived in the form of a small group of worried young architects who called themselves the Chicago School of Architecture Foundation. They managed to raise $35,000, convince the lithographers to sell, and the Glessner house was unexpectedly saved. Since then it has been restored and refurnished (in the latter regard, thanks largely to Glessner family donations) to the point where one might easily assume nothing untoward had ever happened to it.

Below is the side elevation facing 18th Street, with signature Richardsonian Romanesque arch (actually a service entrance) visible at its western end. 1800 South Prairie Avenue was the last project in the illustrious career of Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886). Is it coincidence that Richardson weighed 370 pounds and his buildings all looked like... well, like this? You can't dispute his training or intellectual credentials, or his impact on American architecture. Richardson's fully developed aesthetic was rooted - heavily, we'd have to say - in a combination of the era's Arts and Crafts movement and a scholarly devotion to the Roman antecedents of European architecture. But you either like it or you don't.

Rescue of the Glessner house led to the 1979 creation of Chicago's Prairie Historic District. Despite a near absence of old houses, the district is a leafy and appealing residential enclave located less than a mile from the Loop. The 1800 block of South Prairie, now lined with mature trees, has additionally been fitted out with special sidewalks, street paving, and vintage looking streetlamps. Rigid design guidelines on this one block have produced an unexpectedly authentic coup d'oeil.

Glessner described himself as a "man of moderate fortune," although buying the land and completing his house on it cost a whopping (in 1887) total of $149,000. Not only was Glessner Richardson's last client, Richardson himself would die (at age 47) before the job was done. It was the custom of his Boston practice to offer jobs to the three top architectural students at Harvard and MIT. George Shepley, Charles Rutan and Charles Coolidge were the anointed three when Richardson died. They finished the Glessner job for their dead boss, then continued his practice under their own names, producing, I might add, a very different looking opus.

Richardson's complicated floor plan is predicated on the highly debatable notion that street views are worthless because people cover up their windows anyway with curtains. The fenestration overlooking East 18th Street, for example, has practically been reduced to gun slits. Larger windows peeping between granite blocks over South Prairie do little to soften the fortress-like gestalt. The intended source of sunshine is an interior court whose carriage drive traces the southern property line between Prairie Avenue and a service alley on the west. 1800 South Prairie is kind of somber, but so is the whole Arts and Crafts movement.

The Glessners loved the place, and weren't alone in that opinion. Alongside the naysayers in Mrs. G's diary were compliments like: "Just the sort of house I should build if I could," from Dr. Adams; "I like it exceedingly," from the famous architect Robert H. Robertson; and "I never saw so splendid a house," from a certain Miss Montague. True to the owners' and architect's shared mindset, every detail, inside and out, received a conscientiously "artistic" treatment.

The Glessner children were home schooled in a basement room down a short flight of stairs just inside the front door. Outside grade is at about the level of my sternum. The idea of half burying the room was supposedly an aid to son George's hay fever. (Go figure).

Let's retrace our steps from the schoolroom to the main hall on the first floor.

These main hall windows overlook the interior court. The door between them is for people arriving via carriage, although I wonder if it was used much. The un-sheltered distance from courtyard carriageway to this door is about twice that from the main door on Prairie Avenue to the curb out front.

The Falstaffian image of architect Richardson hangs on the same hall wall John Glessner hung it on in 1887.

Believe it or not, behind Mr. Richardson's picture is a brand new replica of a vanished vintage powder room.

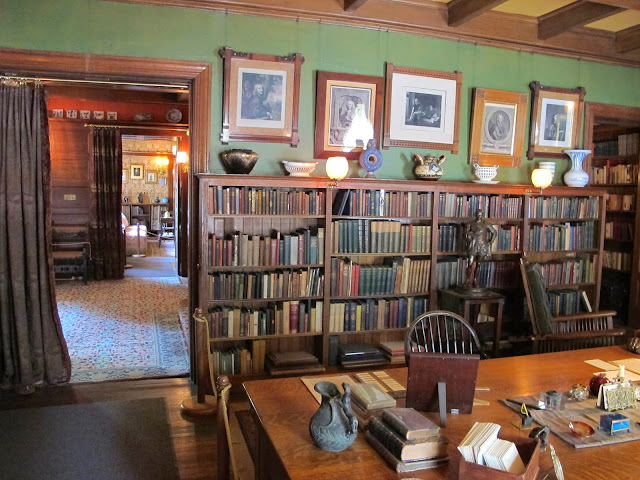

Adjoining the main hall is a library overlooking Prairie Ave. Hard to believe this handsome room was once filled with printing machinery, that it was saved despite being in the middle of an industrial slum, and that even the original furniture, auctioned almost 80 years ago, has found its way back. Mr. & Mrs. Glessner sit tranquilly and with apparently no inkling of what was to come, on the same library sofa that's there today.

A corridor at the south end of the main hall leads to the owners' bedroom suite.

The old bathroom didn't survive, but a picture of it did.

There are stairways all over the house, but this spiral, seen looking down from the landing outside the owners' suite, is the only one that connects all three floors. The children's bedrooms are directly above; the school room directly below.

In the image below, the corridor to the owners' suite is through the door on the right; the stairs down to the school room are behind the urn by the front door; Prairie Avenue is outside; and the balcony over the front door is a gallery.

Twin doors on the west side of the main hall lead to the living room or parlor. Here's another interior that looks amazingly as if the Glessners might be upstairs and down any minute. John & Frances Glessner were serious adherents to the Arts and Crafts Movement, a philosophy of bettering mankind via an anti-industrial discipline of hand craftsmanship. Perhaps by supporting individual craftsmen and surrounding his family with craftsman-made pieces, Mr. Glessner was atoning for his enormous industrial factory. There's a lot of Victorian upholstery at 1800 Prairie Avenue, but it's leavened by William Morris papers on the walls and an abundance of handmade "objets."

Random fact: According to Mr. Glessner, if he had it to do over again, he would have made the dining room bigger.

The pantry is fabulous, as is the kitchen.

The door on the left in the image below leads down to what started as a stable and eventually became a garage.

Next stop, the second floor.

Son George and sister Fanny's rooms, together with 2 guest bedrooms, radiate off the second floor landing.

The odd fireplace seen below is located in the principal guestroom at the northwest corner of the house. It only looks odd to us. Aesthetic Movement types swooned over this sort of artisanal quirkiness.

The second guestroom wasn't designed with an en suite bath, which Mr. G. also later acknowledged as a mistake.

Happily, Lithographic Technical didn't gut the place during its stint as a printing plant. However, they did knock the wall down between Goerge's and Fanny's bedrooms. It's still down, the idea being to eventually convert the space into a display area.

So much is so perfect in here that it's a shock to come across an un-restored corner.

Now we're back on the 2nd floor landing. That sliver of door on the right used to lead to George's room; the door beside it goes to the guestroom with the lopsided fireplace; the 2nd guestroom is across the hall on the left. All the way in the far corner is the entrance to a corridor leading first to the conservatory, and continuing on to servants' quarters.

Restoration of the Victorian glass conservatory is a project for the future.

Beyond the conservatory is a warren of maids' rooms on top of the kitchen suite. Beyond them are male servants' quarters which shared the area over the stable with a hayloft. These rooms were partly dismantled over the years and incorporated with the former hayloft into what is now an attic full of architectural salvage.

En route back to the 2nd floor landing we'll make a quick detour to the 3rd floor penthouse where the butler lived. Not much to see, I'll admit, as it is now a site office. Another of Mr. Glessner's reflections on his otherwise perfect house was that the butler should have had his own bathroom.

I couldn't leave without seeing the basement (no surprise), a feat which would have required Global Positioning assistance, but for the help of my patient and hospitable guide, site Executive Director Bill Tyre.

The basement is mostly storage (zzzz....); the laundry room is now a gift shop.

As I wrote this piece, I imagined Mr. Glessner a week before his death, days before his 93rd birthday, alone in his big old house. It is January 1936, his wife and son are dead, and his beautiful neighborhood has become a wilderness of vacant lots, abandoned mansions and belching factories. Not surprisingly, his 58-year-old married daughter has no desire to move back. It could be a scene from Peter Sellers' 1979 movie, "Being There." Chance lovingly nurtures the old man's garden while the outside world crumbles into a howling slum. The story of the Glessner house, fortunately, has a happy ending. An independent foundation called the Glessner House Museum now manages both it and the city-owned Clarke House, a serene wood frame Greek Revival built in 1836 and located in a parklet right behind Glessner. Quite a contrast between the two; the link for both is www.glsssnerhouse.org