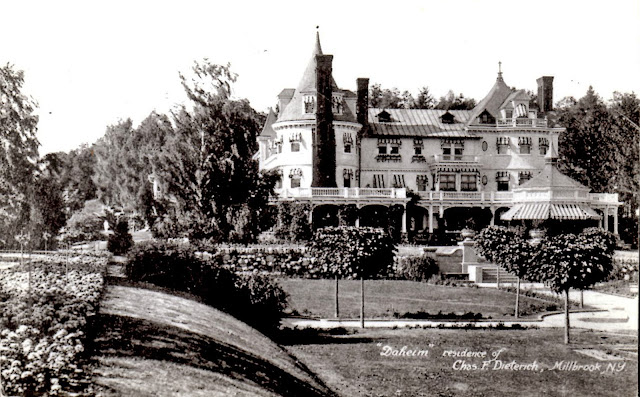

This is where I live in Dutchess County, on an estate called Daheim. The early postcard view above, taken in about 1900, shows a maintenance monster of the High Victorian persuasion, still smelling of fresh lumber and new paint. The main house is part of a suite of buildings displaying innocent charm in spite of clumsy siting and an unimaginative landscape. A Swiss Chalet style bowling alley flanks the mansion on the left, a large carriage house with male servants' quarters is on the right, a tennis court with picturesque adjacent pavilion occupies a broad terraced lawn up front. Was there a distant view from the house? That would be a yes, or at least there would have been (of an artificial lake), had the view not been blocked by the fence around the tennis court.

A hundred and fifteen years later all these buildings are miraculously extant, if now selectively screened by trees. The composition of today's view is much improved. Well, to you the place might look a little blowsy, but it took 33 years to get it back to this. People are forever gazing at my house and saying things like, "This must really have been something, once," or, "Can you imagine what it used to look like?"

Here's my house on the eve of the First World War, looking as snappy as it ever would. In 1889 Daheim's builder, Charles F. Dieterich (1836-1927), a man enriched by acetylene gas and presidency of the Union Carbide Corp., joined a few like-minded friends who were developing estates around the Hudson Valley village of Millbrook. I've lived in Mr Dieterich's house for almost as long as he did, the principal difference between us being his 200 day laborers and full time house, garden and farm staff, compared to my one live-in caretaker, Bill. My Daheim is an essay in missing pieces - balustrades, awnings, window boxes, fretwork, elaborate constructions on the porch roof, etc., etc., not to mention extensive formal gardens. Like the hair on a man's head and ankles, these things just seem to get rubbed off with the passage of time.

The statue in the middle of the fountain, as they say, "grew legs." I could do better than what's there now, I know, but so much else needs attention.

The fence around the tennis court bio-degraded many years ago and the court itself lawned over. No great loss. When the weather's dry, the court re-emerges as a neat yellow rectangle in the middle of the lawn. A sunken garden located behind - and about 15 feet below - the tennis house originally baked in unblocked sunshine from the southeast. Evergreens planted on the perimeter during the Depression have grown to Rockefeller Center Christmas tree size.

Here's the tennis house with the tennis court, but without the towering trees. Honestly? I like it better now.

The old Dieterich estate still covers over 2000 acres. Besides the mansion, carriage and tennis houses, it includes a gatehouse, farmhouse, gardener's cottage, model dairy barn (the size of a city block), pump house, underground reservoir, 500-foot glass fruit house (minus the glass), 1500-acre deer park (can you imagine? a park for rats with hooves?), a second mansion designed by Addison Mizner and 12 miles of private roads - all of which, if no longer quite in original condition, at least still exist. To provide temporary owner's quarters, architect James E. Ware (1846-1918) slapped a Queen Anne-ish tower on the west side of an existing farmhouse and wrapped the result with a porch topped on the west with a 2nd floor pergola, and on the east with a faintly Thai-looking pagoda. The temporary house was to be replaced with something grander, as soon as a slew of brooding stone, timber and stucco ancillary buildings were completed elsewhere on the property.

Apparently Mr. Dieterich became fond of the temporary house, for instead of pulling it down, he kept architect Ware busy making additions. Ware did a lot of business in Millbrook, an odd fact since his professional reputation rested on urban warehouses and tenement buildings. That said, the second incarnation of Daheim, seen below, is, to my eye, particularly satisfying. The round tower on the left, with the pseudo-Loire-ish look so beloved by American builders in the 1880s, has been balanced by a second tower on the right, full of late 1890s Colonial Revival chic (oval windows, Palladian dormer, bow front).

Too bad about that statue in the fountain. This one, however, located on a secondary drive, has managed to stay put. An old fellow appeared at my door some 25 years ago - his father had been the head gardener - and told me the statue had been a gift from Dieterich to his granddaughter. Well, maybe. Back in 2011, while researching "Old Houses in Millbrook," (published by The Millbrook Independent, and a pretty nifty book, if you can find a copy), I discovered that the statue is located at a pivotal measuring point in the Great Nine Partners Patent. What three naked putti dragging a terrified rabbit out of a bucket have to do with the Nine Partners is unclear, so maybe it was a gift and its location is just a coincidence.

On the eve of the First World War - a date I infer from the car in the second image below - a third floor was added between the towers. Simultaneously, a large steel frame, stone-clad kitchen, servants' and heating plant wing went up in the back. The new third floor is supported by I-beams hidden behind wooden boxes tricked up to look like pilasters. Without steel supports, the additional bedrooms, full tile bath, closets, hallways and large new attic - not to mention the copper roof - would undoubtedly have crushed the old farmhouse below. The result is imposing, but the design was better without it.

In 1927 Charles Dieterich died, and in 1929 his son Alfred, who had abandoned the East and an unfaithful wife for a new life in California, sold Daheim to a small private millionaires' club called the Millbrook Associates. Nine days later the stock market crashed. When the dust settled, two of the original nine Associates were left standing - Walter Teagle (1878-1962), president of Standard Oil of New Jersey (that's him below, on the cover of Time Magazine), and Garrard Winston (1882-1957) a New York corporate lawyer and Under-Secretary of the Treasury under Coolidge. For the next 30 years, these men used Daheim to shoot birds. Winston stayed in my house, Teagle in the grander Mizner mansion.

Winston called my house the White House. Seen below in the early 1930s, it has already undergone a bit of de-Victorianization. The balustrade has been removed from the porch, the Thai roof and the pergola are both gone, and so is the original fretwork between the porch columns. The evergreens haven't yet been planted between the tennis lawn and the sunken garden. Mrs. Teagle maintained the latter during this period almost to Dieterich standards. She employed 5 full time gardeners, cultivated 1600 different types of lily, and opened the garden to the public on weekends.

A fate too good to be true, you say? Boy are you right. After Teagle's death, a local investor flipped the estate to a pair of young heirs, whose sister had fallen under the spell of Harvard's charming and notorious Dr. Timothy Leary. What had started as the Harvard Psilocybin Project led first to Leary's expulsion from Harvard, then to the founding of the League for Spiritual Discovery (get it? L.S.D.?) at Daheim. An initial ivy league collegiality deteriorated at warp speed, culminating with Leary's flight from Millbrook (and future Watergate felon G. Gordon Liddy) to Oakland, California and sanctuary with the Black Panthers. Meanwhile, Daheim was abandoned to a squabbling set of self-proclaimed "gurus" who'd been left behind.

Leary borrowed the white horse from my neighbor, Milt. When Milt checked on the horse in the morning, he discovered it had been dyed pink.

By the late 1960s, the last of the hippies got the boot, the house was boarded up, and nothing happened for over ten years. Then in 1982 I came along and signed a long term lease. By the mid-1980s I had managed to get most of the exterior painted.

You can't tell from the image below, but Daheim really needs to be painted again. Would that I could put that pergola back on top of the porte cochere.

When I saw it for the first time in late 1981, Daheim was looking pretty grim. The pipes had burst, the boiler was a cobwebbed dinosaur sitting in a pit of stagnant water, the windows were boarded up and the interior crammed with storage. Oak and mahogany doors were secured by shiny padlocks whose hasps had been fixed to the woodwork with 12-penny nails . I was asked more than once why I chose to leave a Beaux Arts mansion in Tuxedo Park with 17 fireplaces, to which I replied that this was a "fluid" period in my life.

Life's crises have a way of passing, and if there's one region in which I've had consistent luck, it's where I've lived. The first image below shows Daheim today; the second was taken twenty years ago, when I had almost (but not quite) got it painted all the way around.

For a while, bowling was a fashion amongst the rich and no small number of old places, both in town and in the country, had private alleys. Mr. Dieterich's was right behind his house. It was/is a highly picturesque affair in the style of a Swiss Chalet, designed in 1896 by James E. Ware. It contains two alleys, an upstairs billiard room (replacing a less elaborate one in the main house), and below-grade pre-refrigeration era food (and perhaps ice) storage vaults. Now socked in by trees, it remains amazingly intact. (Actually, it had degenerated into the same ruinous condition as the house, but it's been restored).

When I moved to Daheim in 1982 the walled garden behind the palisade of trees in the image below was completely choked with honeysuckle bushes. Its original look had vanished.

Years of arduous clearing has converted it to a lawn whose grassed-over paths are lined with apple trees. The image below was taken from the exact spot as the vintage view above. This garden is where Mrs. Teagle raised her 1600 lilies. Designed originally as a sun cup, it is now shaded by 80-foot evergreens planted in the late 1930s along the perimeter wall.

Here's another good "before and after," looking north up the spine of the garden towards the carriage house. Daheim is just out of sight on the left.

Nor were these the only greenhouses on the property. The image below shows the 500-foot fruit house located about half a mile from the main house. The glazing is gone but the stonework has been stabilized.

The original gardener's cottage might be architect Ware's most appealing design on the property. Identical shingles on walls and roof originally gave it a voluptuous look.

There've been an awful lot of changes to my porch, but the view from it is still beautiful.

The Dieterich ladies are long gone...

...and so is he....

...and she is too (now married with children)...

...but I'm still here, at least for now.