"I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately," Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) wrote in 1845. Sidebar: Did you know his name was David Henry Thoreau, and he changed it to Henry David? Or that it was pronounced THOR-row, which rhymes with Storrow? "I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life...to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner." To which end, for two years, he lived in a hut by Walden Pond.

In 1862, the year Thoreau died at Concord, Mass, a different sort of fellow named Ogden Codman (1839-1904) reclaimed an ancestral estate (which sounds grander than it was) in nearby Lincoln. Codman is seen below in 1864 with his wife, Sarah Bradlee. "The Grange," as he named the new/old country seat, was almost exactly as far on one side of Walden Pond as Thoreau's Concord was on the other. Residential proximity aside, Thoreau and Codman were light years apart. One lived in the world of ideas; the other lived decidedly on earth, aided by a family fortune derived from the sea trade and Boston real estate.

The Codmans had six children, five of whom survived. The most celebrated was Ogden Codman Jr. (1863-1951), a society decorator who championed 18th century classicism in an aesthetic world besieged by 19th century excess. Who among us can honestly claim to have heard of the Great Boston Fire of 1872? (Not me). This epic conflagration, which obliterated 65 acres of downtown Boston, delivered a major hit to the Codman family treasury. Their cost-cutting response was typical of upper class Americans of the day; they moved to France. Sensitive and artistic OC Jr was 12 at the time. Nine years in the American colony at Dinard would inevitably influence his sense of aesthetics.

After several unenjoyable apprenticeships, Codman opened his own Boston office in 1891 at age 29. His practice grew through the '90s, stepping up a notch in 1893 with a do-over of author Edith Wharton's Newport cottage. A bigger boost came in 1894 when Codman was hired to decorate the second floor of Cornelius Vanderbilt's new Breakers, a fat and influential commission if ever there was one. In 1897, he collaborated with Wharton on a book titled "The Decoration of Houses," a watershed event in decoration and in Codman's career. "Houses" argued persuasively that good decoration is inherently architectural, that it is not, as Edith put it, a division of dressmaking. The book remains a classic today.

The Grange started life in the late 1730s as a 2-story Georgian provincial farmhouse of modest pretension belonging to a man named Chambers Russell. Russell's Tory grandson skipped town for Antigua during the Revolution, after which the property was inherited by a related minor child named Charles Codman. The child's father, John Codman (1755-1803), "federalized" the house, turning it into a 3-story cube with the assistance of Boston architect Charles Bulfinch. Mr. Codman, whose grandfather it is (perhaps) interesting to note, was poisoned by his own slaves, died in 1803, and by 1807 his son Charles, no longer a minor, had liquidated the property and set off on a life of expensive pleasures elsewhere. Here's the Grange in the 19th century, looking almost exactly as it does today.

In 1862, after 55 years of assorted non-Codman owners, newly married Ogden Codman Sr. fulfilled the burning desire - very much an American one for our 19th century grandees - of reclaiming the estate of grandfather John Codman. Together with his architect brother-in-law, John Hubbard Sturgis (1834-1888), Ogden Codman improved the grounds and outbuildings, and upgraded the house with, among other things, indoor plumbing and a Victorian paneled dining room.

In 1888, Codman enlarged the house with a gambrel-roofed kitchen, laundry and maids' wing that extended to the north. His children gravitated around the Grange throughout their lives, unencumbered by spouses, with the exception of Ogden Jr. who, in 1904, wed a rich widow with a Manhattan townhouse he'd designed for her late husband. OC Jr. tinkered with the Grange's interiors throughout the 1890s - what else would a decorator do? - toning down the Victoriana of his parents' early days and emphasizing the building's 18th century bones.

To the west of the house, occupying a sunken site more accessible to servants than family, is a delicious Italian garden laid out in 1899. It was a pet project of the senior Mrs. Codman (1842-1922), although I assume crucial design decisions were left to her decorator son.

The columns at the west end of the pool are salvage from the ruins of the Codman Building, destroyed in the Boston fire of 1872.

Like every big old house, the Grange needs a lot of TLC.

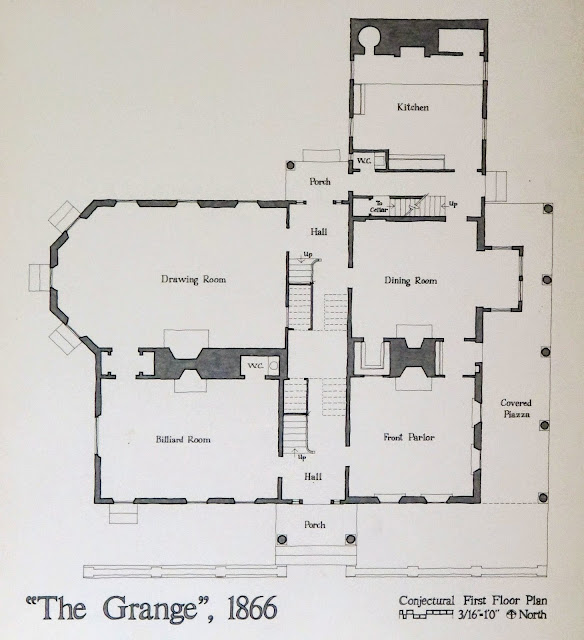

The front door is a good place to pause and compare evolving floor plans - well, at least for the first floor.

The Chambers Russell house was a simple affair in 1741, the second floor largely a duplicate of the first.

In 1790, John Codman didn't just add a third floor, he doubled the structural footprint with a bow-fronted "hall" - occasionally used as a ballroom, we hear - plus a kitchen annex in the back. Rather than rebuild the staircase to provide access to rear rooms on expanded upper floors, Bulfinch attached an inventive "mirror addition" on the north of it.

55 years later, when the house came back into the Codman family, architect Sturgis tacked a box addition onto the southwest parlor, making it into a billiard room, and balanced it with a porch on the east.

When the new kitchen and maids' wing went up in 1888, the old kitchen became the servants' hall.

The most unusual feature of the Codman house is the inventive and highly decorative staircase. A window at the northern end of the hall was replaced in the early 20th century by an elevator, alas at the expense of needed natural light.

The southeast parlor, which the Codmans called the Morning Room, preserves beautiful paneling from 1741.

The library is across the front hall from the morning room. OC Sr. used it as a billiard room; OC Jr. exiled the table and filled it with comfortable furniture and books.

The door to the left of the library fireplace leads into the bow fronted "hall" on the 1799 plan which, by 1866, had become a drawing room. By 1963 all the Codman siblings were dead, except sister Dorothy. She stayed on at the Grange until her own death in 1968, after which the property was donated to the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (today's Historic New England) with absolutely everything still inside of it.

The image below shows the back half of the double stair, looking towards the front door. We're making a clockwise tour of the first floor. Next stop, the dining room.

OC Jr's Uncle Sturgis is said to have played an important role encouraging young Codman to pursue a career in design. Charming artifact or not, the Sturgis-designed dining room, with its dark woodwork and ponderous details, is just the sort of room Codman wouldn't like.

A door on the north wall of the dining room leads first to a service corridor with back stair, and then to a servants' hall. The over-scaled hearth, pot hanger intact, speaks to the room's original 18th century use as a kitchen.

Further on is the 1888 addition whose finishes, in serving pantry and in what the Codmans called the "new" kitchen, speak eloquently to the Victorian era. At the time of Dorothy Codman's death in 1968, the new kitchen had hardly changed.

Through a door on the kitchen's north wall is a corridor to the laundry room.

It's a long hike from laundry room to main stair, and an interesting hike to the second floor.

There are 8 principal bedrooms - 4 on the 2nd floor and 4 on 3rd - and not quite enough bathrooms. The senior Mrs. Codman's room is on the southeast corner of the 2nd floor. She had her own bath en suite.

A shared closet connects Mrs. C's room with that of her musical (and rather sheltered) son, Hugh (1875-1946).

The door from Hugh Codman's bedroom to the hall illustrates the necessity of the double stair. We'll descend to the mezzanine level in the middle distance, then climb back up to the landing at the front of the house. Mother Codman's bedroom is on the left (southeast); sister Alice's (1866-1923) is on the right (southwest).

Alice Codman's bedroom, to my eye, is pure Ogden Codman Jr. - bright, elegant, erudite and extremely comfortable. But she doesn't have her own bathroom.

Nor is there an en suite bath for this guestroom, located above the drawing room on the building's northwest corner. Alice and guests alike trekked to a hall bath by the back stairs.

Distributed above the kitchens and laundry is a former nursery, a gaggle of maids' rooms, a small servants' lounge, 2 back stairs, and one very modest bathroom.

We're back on the main stair, looking south towards the front of the house, about to visit the 3rd floor.

Ogden Codman Jr's room was on the southeast corner of the 3rd floor, directly above his mother's. After six years of marriage, Codman's wife, the former Leila Griswold Webb, died in 1910 at the age of 54 (Codman was 47). In 1920, he abandoned the States - together with a client list that included names like Cabot, Coolidge, Otis, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Paine - and moved permanently to France. It was here, in 1944, that an aide to General Patton discovered him in his suburban chateau, reading in bed while the Nazis fled Paris outside his window. He spent his last years embellishing a spectacular Riviera villa called La Leopolda, which he rented out but never personally occupied.

The southwest bedroom belonged to brother Tom (1868-1963).

And the northwest room on the third floor was Dorothy's (1883-1968). She died here at the age of 85, 48 years after Ogden left, 46 years after her mother died, and 5 years after the last of her siblings, brother Tom, passed away in 1963.

Across the hall from Dorothy's room is another hall bath,, this one shared by everybody on the 3rd floor except Ogden who, like his mother, had his own en suite. Next to the hall bath is the simple bedroom of Marie-Reine, Dorothy's French nanny who stayed with the Codmans for the rest of her life.

The family's trunks are still in the attic.

Shelves full of preserves - probably about to explode - are still in the basement.

My guides from Historic New England, Wendy Hubbard and Susanna Crampton, were not only infinitely patient and helpful, but understood completely that I wanted to see EVERYTHING. Historic New England owns 35 house museums, huge collections of art and artifacts, and important archives documenting New England architectural and social history. One of its early members, when still called the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, was Ogden Codman Jr. In 1920 Codman convinced the rest of the family that the Grange deserved preservation. A lucky thing for us all. The link is www.historicnewengland.org.

Now this one was really fascinating! Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThe interiors are pure Codman, very much what he and Edith Wharton were proselytizing in their influential book. The society decorator Elsie de wolfe ("I believe in lots of optimism and white paint") took up the cause in a rather more flashy way, popularizing it through her own books and media coverage. And you still see this style, lots of chintz and bits of French furniture, in old-money spots like Fairfield County, CT.

And that staircase is something to behold!

Historic New England does great work.

Thanks! That was interesting! I loved the back story. What was going on with the floors? It looks like sisal (?) was glued on many areas and other had black over the wood as if something had been removed. I'd love to know because in the first bedroom we saw (the senior Mrs. Codman) it looked like the floor boards were almost 12 inches! Thank you!

ReplyDeleteI believe the matting material is coir, a plant material like sisal that was used by British country folk as a sub-flooring. I've never seen it glued down to the boards -- usually it's simply cut and laid, almost like Japanese tatami.

DeleteOne of your most memorable posts. Everything is still there for us wonder at and to catch our breath, the famous son and his family's home preserved in amber. It's all just...as we would have hoped...beautiful, satisfying, wistful.

ReplyDeleteA lovely house that still has the air of a home.. But a touch of melancholy too, with Dorothy, the last Codman, alone there at the end of her life.

ReplyDeleteWhere are your booties John Foreman? Exceptional house, exceptional post!

ReplyDeleteI agree with the comment above by Glenn. The home is lovely but does have an air of sadness and melancholy about it. Hopefully there was always some fresh cookies and milk in the kitchen to cheer the atmosphere.

ReplyDeleteConcerned as he undoubtedly was with preserving The Grange, O.C. Jr. also at one point envisioned a radical remodeling which would have transformed the rambling east front into an architecturally coherent whole, complete with central pediment, at the cost of much of the house's character. Thankfully either the project proved too much for his purse or his conscience got the better of him; perhaps both in equal measure. A booklet published by SPNEA illustrates the scheme; regretfully I don't own a copy.

ReplyDeleteWhat a splendidly inventive and attractive staircase! It would be a pleasure to dust it (with a long-handled feather duster inasmuch as I'm no longer comfortable doing the 'staircase bump').

ReplyDeleteHas anyone ever heard of the convention that landscapes belong in the lounge whereas still lifes are hung in the dining room? There are nice little pictures hung all over this house!

Melancholy? What the house needs is a pack of Corgis, several cats and huge vases of flowers! And Douglas is absolutely correct about the fresh cookies, but I'd prefer a nice berry crumble...

Oh, wow, amazing. As usual, I am as much or more intrigued by the back stairs, attics, servants' quarters, and cellars as the formal part of the hosue.

ReplyDeleteAnd speaking of the many hanging pictures - interesting to see they are hung in the Victorian style - from the picture rail.

ReplyDeletePS - and speaking of that pompous overrated little twerp Thoreau in his so called wilderness shack. He took his wash home on weekends for his mom to do and due to the depletion of the colonial forests, was able to see downtown Concord from his doorstep "deep in the wild". The original back to the lander and just as authentic.

ReplyDeleteLaunching function of the book is firm for the matter for the success. The style of theInvestor Day Productions

ReplyDeleteis ensured for the team. Struggle is done for the top of the turns for the weighed element for the turns for the individuals in tis ambit.