None of my great-great-grandfathers was a Victorian world beater. Not even one earned the several millions - when a million was more like forty or fifty - that would anchor his DNA heirs in a world of entitlement, good clubs and valuable real estate. My mother's family was admittedly distinguished in the antebellum South, if for all the wrong reasons. However, her branch was broke. And my dashing explorer father was a first generation immigrant with no background at all. I was never drawn into the gravitational orbit of a "good" family, never returned year after year to some grand summer house run by a patrician old lady to whom I happened to be related. Black Point, a lake house on the (unexpectedly, to this eastern provincial) luxurious shores of Wisconsin's Geneva Lake, is an example of what I missed.

This beloved maintenance monster, designed originally with 13 bedrooms and one bath, was completed in 1888 on 28 lakefront acres by a German immigrant turned Chicago beer baron named Conrad Seipp (1825-1890). The architect was another Chicago German named Adolph Cudell (1850-1910). A number of Cudell's ponderous Victorian city mansions, including a quarter of a million dollar stone pile for Mr. Seipp, once ornamented now unrecognizable neighborhoods in Chicago. After the great fire of 1871, the fashionable village of Lake Geneva on the shores of Geneva Lake (there's an explanation for the word shuffle, which we shall simply omit) became a magnet for Chicago - and, to a certain extent, Milwaukee - money. And so it remains today.

The images below show the back of the house, today and before 1945. A large kitchen, laundry and service wing, demolished after the war, was replaced with a simplified kitchen that is today a gift shop. The double windows on the back of the house overlook the main stair.

Nowadays you can drive to Black Point, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries the family arrived by boat, and not just any boat. The year after Die Lorelei, as the house was originally called, was completed, Mrs. Seipp commissioned construction of an elegant lake steamer whose name she anglicized to Loreley. The boat picked up family and guests - thirty or forty at a time - from a private dock in Williams Bay, on the other side of the lake near the train, and deposited them at the foot of a sloping lawn that leads to this staircase.

Here's a face I'd call "determined." Conrad Seipp emigrated to Chicago to escape revolutionary upheavals in Europe. The small Chicago brewery he bought at the age of 24 evolved, 20 years later, into the Conrad Seipp Brewing Company, fifth largest brewer in America. Along the way Seipp had 2 wives, 7 children, built a mansion in Chicago and another in Wisconsin. By 1890, his brewery was producing 100,000 barrels of beer a year. That summer, he spent his one and only season at his new Wisconsin lake house. He contracted a fatal case of pneumonia in the fall and died at the age of 65.

So actually Die Lorelei was the summer home of his widow, Catharina. Every year she gathered her multiplying family - or as much of it as she could - to her great barn of a lake house for a family vacation. Once inside, the first thing you saw was a great etched "CS" on the inner foyer doors. It has never occurred to me to blazon my initials on the walls or doors of my house. However, I've just lived in big houses; I've never actually built one.

I like the color of these walls - slightly dowdy but so authentic. Masury makes a color like it called "Sea Foam," which I use for touch-ups at Millbrook - when I actually do touch-ups. Despite the exotic stick style exterior, Black Point's first floor doesn't differ much from your basic 18th century center hall colonial. There are front and back parlors on the right, a dining room and billiard room on the left, and a pantry and kitchen in the back. Let's look first at the front parlor, furnished like the rest of the house with original pieces. This heat-less structure has always been closed in the winter. It's only mid-April now and the curtains haven't yet been rehung.

When America finally waded into the First World War, Mrs. Seipp and her family decided "Die Lorelei" was an impolitic name for an American house. They changed it to "Black Point" which, to me anyway, seemed at first a kind of left turn. Its genesis is an obscure Potawatomi word referring to the property's numerous black oaks. Ergo, "Black Point." The wide doorway with the portieres in the image below connects the front and back parlors.

Opposite the back parlor, on the other side of the hall, is the dining room.

My boyhood friend Bob and his wife Nana stand by the door connecting the dining room in the back of the house to the billiard room in the front. First, however, we're detouring to a screened porch outside the door next to the fireplace. The big bell on the wall behind our hostess, Mary Kaye, came from Mrs. Seipp's boat.

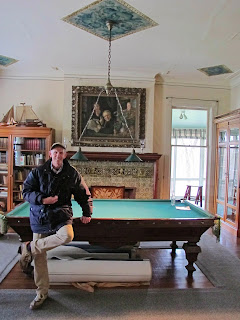

The billiard room is cold! And I haven't a clue where they got that wild and crazy picture.

Black Point's serving pantry is located at the end of the hall under the stairs. It's connected to the dining room on the left side of the hall, and the kitchen wing at the back of the house. Dinner chimes are mounted on the wall outside the pantry door.

The pantry connects to a landing at the foot of the servants' stair. The latter is practically outdoors, tacked onto the back wall of the main house, and rising to a mezzanine landing on the main stair.

Those dazzlingly white floor length dresses favored by Victorian women, not to mention the multiple layers worn even in warm weather by their menfolk, generated laundry on an Olympian scale - especially in a house with 40 family members and guests. Black Point's original kitchen, servants' and laundry facilities were housed in an attached two-story structure of some size. As decades passed, not just the clothing but the expectations of guests and availability of servants all changed. At the end of the Second World War, the largely unused service wing was torn down and replaced with a sort of "I Love Lucy" kitchen, now a gift shop.

Time to go upstairs. Worth noting en route is the curious interior treatment of the double height window lighting the stairs.

When the house was built, as noted earlier, there was exactly one bathroom. Here it is, located half way between the first and second floors, next to the door to the servants' stair.

At the top of the stairs, a long second floor corridor is lined with closets full of nifty junk and interspersed with doors to bedrooms - and more bedrooms, and still more bedrooms.

Catharina Seipp, the dowager of Black Point, is seen below surrounded by a handful of her many family members. These people bore names like Schmidt, Madlener, Bartholomay, Reese and Petersen and they all needed beds. Luckily Black Point had plenty.

Electricity was installed in 1917, and more bathrooms were eventually shoe-horned into the existing plan.

Many rooms in the house look as though someone just walked out and might return any minute.

The third floor is much like the second - bedrooms and bedrooms, baths and baths - albeit a tad less desirable.

I think we've seen it; time to go.

Nana's checking email first.

Brewery money gave Conrad Seipp's descendants a leg up in the world, but eventually it ran low and finally ran out. Almost immediately after the founder's death, his brewing operations were folded into a larger firm controlled by British interests. The family were transformed into investors who would eventually suffer from the onset of Prohibition. In 1933, as the ludicrous Volstead Act was about to be repealed, the Seipp's Beer operations went under, the brewery was razed, and a hospital rose on the site.

In 2005, Conrad Seipp's great-grandson William Petersen, gave Black Point, together with all the furniture and 8 acres of lakefront property, to the state of Wisconsin. It's been open to the public (summer only; there's no heat) since 2007. There is a certain sadness about a big old house, enjoyed by generations of family members, leaving private hands and becoming a museum. However, that sadness is offset by the undeniable pleasure that strangers get from seeing it close up. What's that rock in the image below? It's the cornerstone of the demolished brewery, hauled up to Lake Geneva and set into the lawn at Black Point. If you're out this way, be sure to visit; the link is www.blackpointestate.com.