It didn't look like this, that's for sure. In a few weeks I'll be speaking at the University Club, a noble institution to which I belonged for 34 years - and had I hung on for 16 more, I wouldn't have had to pay dues. Actually, I'm just warming up the crowd for my friend, John Kinnear, whose talk is titled "The Scots Who Built New York's Landmarks." (Who knew?) Uncertain how best to complement his topic, and mindful that said Scots worked mostly around 1800, I decided to draw a picture of Manhattan Island as they had seen it. Here, now, is a sneak preview.

This subject fit neatly into my personal interest (preoccupation? obsession?) with old houses. Manhattan, with all that tasty waterfront, once hosted a delicious lineup of country places overlooking the North River, as the Hudson was called, in one direction, and the Sound, as a vanished gentry called it, in the other.

In 1800, most of the countryside north of the city seemed, if not immune to development, then subject to it at a leisurely pace. The infamous Commissioners Plan of 1811 never even envisioned the city as extending beyond 155th Street. Largely rebuilt in the wake of the Revolution, New York surged northward with unexpected ferocity, invading nearby retreats that had been genteel and semi-rural barely a decade earlier, much like Queens and Nassau in the 20th century.

Like a child on a diet of junk food, the place swelled beyond anyone's expectations.

New Amsterdam was a Dutch city with stepped roofs and Holland-ish canals - or at least one canal, later the site of Broad Street. Some Dutch houses survived the fire and pillage of the revolution, and continued to lend antique charm to the New York of 1800. They were, however, a vanishing breed.

Although the map below was drawn thirty-odd years before 1800, it captures the look of the city and its environs, if not the precise size of the city itself. Taking into account the inaccuracies of whim, oversight and/or aesthetics on the mapmaker's part, several things are apparent. For example, this part of the island appears to have been long ago deforested. The picturesquely irregular waterfront once featured high bluffs on the east. I doubt the many orchards were quite so orderly, but the absence of farm fields convinces me that serious food cultivation was no longer taking place this close to town.

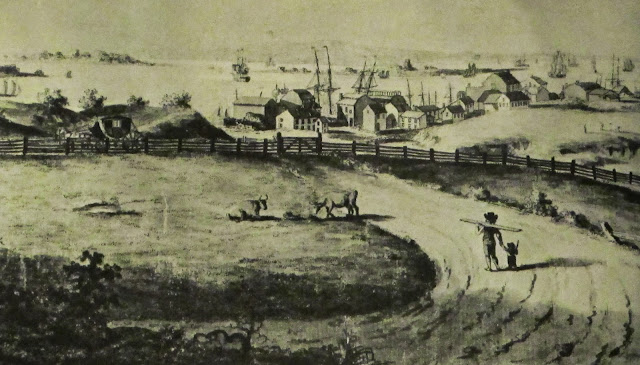

Seen from Brooklyn in 1794, the city looked substantial.

Bowling Green was an upscale residential area. This view looks north up Broadway.

St. Paul's Chapel is as familiar today as it was in 1800. OK, you history purists, I know City Hall wasn't finished until 1811, but these images convey an accurate sense of Broadway's metamorphosis, in the very first years of the 19th century, from residential to commercial.

Nor was Broadway the only busy street in town. The image below shows Broad Street, formerly the Dutch canal, looking north to New York's first city hall, located at the intersection of Broad and Wall. At the beginning of New York's brief stint as the nation's capital, George Washington took the oath of office on the loggia of this building.

In the middle of the image below is Tontine's Coffee House, a local nexus of business, politics, auctioneering, banqueting, gambling and slave trading, patronized by a fierce and free-wheeling population of take-no-hostage entrepreneurs.

The city in 1800 had no lack of surprisingly elegant townhouses.

Bowling Green in 1800 was about to be eclipsed by St. John's Park, today occupied by a complex of ramps that emerges from the earth to debouch travelers from the Holland Tunnel. St. John's was meant to summon the image of an elegant London square, complete with fashionable church and elite residences, the latter regulated by aesthetic covenants and surrounding a "members-only" park. And so it was, at least for a while. The place came to a premature and horrible end, but that's a tale for another post.

Squares and mansions notwithstanding, most New Yorkers lived in humble fire-prone wooden houses built without building codes, effective sanitation, or a dependable source of water.

Until it became too polluted to drink, the city's water came from a once enchanted spring fed lake, 60' deep, covering 48 acres, and called alternately the Collect Pond or simply the Fresh Water. As the developing city grew closer, the Collect fell victim to all manner of disgusting ecological outrages from the tanneries, slaughterhouses and breweries built on its banks. (And we think fracking is bad). In lieu of clean-up and conversion to a city park, as none other than Pierre L'Enfant suggested, the city chose to bulldoze an adjacent 110-foot hill called Mount Bayard into the Collect and divide the soggy result into building lots.

The Lispenard Meadows, a swampy area at the western end of what is now Canal Street, was one of the natural outlets of water from the Collect.

The city, even in 1800, may have been gobbling land rapaciously, but the gobble line, absent suburban sprawl of later eras, marked a clear division between urban and semi-rural. Richmond Hill, a beautiful estate that once belonged to Aaron Burr, stood at the intersection of today's Charlton and Varick Streets, a literal stone's throw from advancing urban skirmish lines. Not everything outside town was so refined, of course, but a very great deal of it was.

Manhattan's eastern shore had a similar look. The Belvedere House was an early prototype of country clubs to come. The location, on a bluff atop Corlears Hook (about 2 blocks south of the Williamsburg Bridge), enjoyed views of sailboats on the East River, Long Island countryside on the opposite shore, and proximity to elite residential neighborhoods on Cherry and Madison Streets.

The Manhattan countryside of 1800 was traversed by a long established network of roads, albeit one that was unimproved and often raggety. By 1800 people had been walking and driving carriages up and down the Bowery for over a century. Broadway north of 14th Street still more or less follows the line of the equally old Bloomingdale Road. The Commissioners Plan made short shrift of venerable Manhattan neighborhoods by burying their lanes and roadways under a relentless grid of right angles.

The mix of farm fields, orchards and meandering roads on the map below is today's midtown. Your best landmark is the southern tip of Roosevelt Island. The little bay with the illegible label to the left of it, located above the "i" in "River," is Turtle Bay. The larger bay to the left of that is now landfill underneath Peter Cooper Village and Stuyvesant Town.

The great majority of Manhattan's shorelines, on both the east and the west, was occupied by country places.

By 1800 the majority of producing farms were up on the Harlem plain. The former Dutch farm hamlet of Bloemendaal, at today's West 100th Street, had become the smart rural retreat of Bloomingdale.

The photo below was taken much later than 1800, but the Bloomingdale Road in the foreground and the riverview manse beyond probably hadn't changed much.

The grandest place at Bloomingdale was the 268-acre Apthorp Farm. The house itself was built in 1764, located on the line of today's West 91st St., and is the namesake of the famous Edwardian apartment building on 79th and Broadway. Developers pulled it down in 1891. I've included a few photos of other early houses, and leave it to my readers' imaginations to visualize their original surroundings.

Equally fashionable, and located directly across the island from Bloomingdale, was Hell Gate. It would be an overstatement to describe Manhattan north of the city as "park-like," but the countryside was gentle and the private places overlooking the two rivers had, in many cases, been loved and cultivated for generations.

Manhattanville was another village, located in the narrow valley of today's West 125th St. The Harlem Heights rose behind it; the farms of Harlem itself lay to the east.

The map below shows the Harlem plain. The village of Harlem is located on the approximate line of 121st St. The lane that runs down the center of it ends at the Harlem Creek (now River). The cut containing Manhattanville is visible between the Harlem Heights on the right and the promontories of what in time would be called Morningside Heights on the left. Harlem Heights was a delectable rural area in the first years of the 19th century. During summers when his family lived at the Grange, Alexander Hamilton gladly made the 2-hour commute each way by carriage to his New York City office.

The last - and most northerly - house of any importance on the island was built in 1765 by a British Colonel named Roger Morris. This was Washington's headquarters-on-the-fly, in the wake of disastrous battles to the south. It was later owned by the widow of a high liver named Stephen Jumel. The widow married Aaron Burr in this house, an event humorously described by Gore Vidal in his historical novel "Burr" which, if you haven't already, is a terrific read.

Not much was happening at the northern end of Manhattan in 1800. Several features in the map below are (to me, anyway) of interest. That's the Hudson, running north and south on the top of the map. Fort Washington Avenue and the Cloisters occupy the high ridge on the top left. Across the narrow cleft of today's Dyckman Street, is Inwood Hill Park. Interestingly, the forests of 1800 - if not the exact trees - still cover most of these two heights. Spuyten Duyvil Creek, whose serpentine curls once separated Manhattan from the mainland, was replaced in 1895 by the useful but boringly widened Harlem Ship Canal.

So that's approximately what the island was like in 1800. Throughout my life I have had dreams where I walked through northern Manhattan in its rural/suburban past. One night I stared so intently at a certain house on what I thought was Fort Washington Avenue that I made an appointment the next day at the New York Historical Society in an attempt to find a photo. (No luck). The physical realities of Bloomingdale, Hell Gate, Carmansville, Harlem Heights, Audubon Park, etc. were once so intense. They were places that meant things to people, had histories of their own, and now they don't exist. Such are today's "Deep Thoughts by John."

Author's note: The very best and certainly the most readable history of New York in my library is "Gotham, A History of New York City to 1898" by Edwin Burroughs and Mike Wallace, published by the Oxford University Press in 1999. Besides being fun and enlightening, it is the authoritative source for all matters pertaining to pre-consolidation New York.

Just...wonderful. Thank you for showing what was that is vanished.

ReplyDeleteHi John,

ReplyDeleteI'm a big fan of your blog, but don't you mean Kipp's Bay as just above Stuyvesant Town? Turtle Bay is the one further north.

You are so right; it's Kips Bay. Turtle Bay was/is further north. I am bad.

ReplyDeleteThis post is so enchanting I paused to add a suitably period musical background -- wish I could dub your voice-over narration as well!

ReplyDeleteMyself being from the West Coast, to me this is like a foreign country. Nevertheless this post is very interesting. Most enjoyable.!

ReplyDeleteI am a huge fan, thanks to Frances in Easton.

ReplyDeleteCome visit us in Philadelphia!

Best,

Liddy Lindsay

Very cool! I'm trying to date our greek revival in the Hudson Valley and I was surprised how many early greek revival styles were in Manhattan. Thanks for publishing a great blog!

ReplyDeleteI look forward to your posts each week.

ReplyDeleteAmazing . Desert Safari

ReplyDeleteDo you happen to know the current location of what was known as "Old Jans Land" back in the 1600s?

ReplyDeleteThis is such a great resource that you are providing and you give it away for free. I love seeing blog that understand the value of providing a quality resource for free.best wishes from Water Filters UAE

ReplyDeleteRead your articles, you are a great Writer who write the all details with his honesty and heart. Also i just have seen a another website which provides me the details that. where should I visit with my children In Dubai" when i had searched on Google i Got a website which help me a lot.

ReplyDeletegreat post

ReplyDeletevery historical thanks for sharing with us bus rental Dubai

ReplyDeleteStainless steel mixing bowls are an absolute requirement in the kitchen. They are multipurpose, durable, and easy to clean

ReplyDeleteVery interesting!

ReplyDeleteinteresting blog Bus rental Dubai

ReplyDelete