Here's a question I've had for years: Why was his name "Johns" Hopkins? Back when I was in college, my fraternity brothers used the first syllable of each other's last names, with an "s" tacked to the end. Thus, Jim Schumann became "Shoes," Nick Brazeau (for convenience) was "Braz," and I was "Forms." Johns Hopkins, however, had more legitimacy; his great-grandmother's name was Margaret Johns.

Born to Quaker parents on a Maryland plantation, Hopkins (1795-1873) became a Baltimore millionaire philanthropist and all around mover/shaker, parlaying a family provisioning business into a fortune in railroads (specifically the Baltimore and Ohio) and banking. Six years before he died, Hopkins incorporated the Johns Hopkins University and the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Each was to be funded by his estate which, at the time of his death, came to a cool $7 million. Hopkins went to the grave a bachelor, reportedly carrying a torch for a first cousin his Quaker religion forbade him to wed. (We'll leave that one alone).

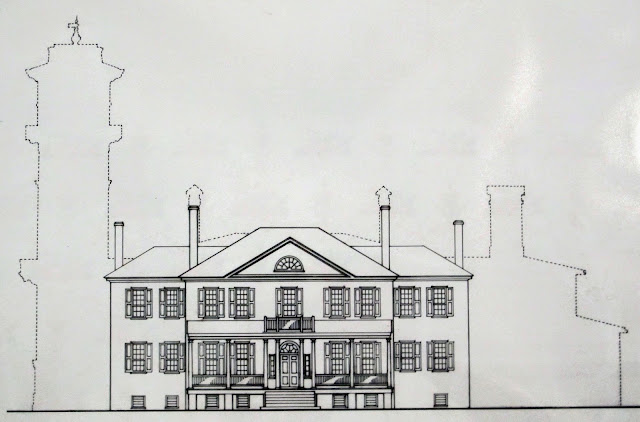

The elevation above shows Clifton, a provincial Georgian country house built in 1803 by a captain in the War of 1812 named Henry Thompson. Clifton stood on 165 acres on the Harford Road, once northwest - and now firmly in the middle - of the city of Baltimore. The house was originally one room deep and 5 bays wide. Flanking wings were added in 1805, and an octagonal dining room to the rear in 1812. In 1837, hankering for country air, the prosperous Johns Hopkins bought the place - at public auction, bad luck for the Thompsons - for $15,800. Between 1841 and 1853 architects John Rudolf Niernsee (1814-1885) and partner James Crawford Nielson (1816-1900), designers of railroad stations for the B & O, transformed Clifton into an Italian palace, the most notable feature of which is a memorable 81-foot tall campanile perched atop the porte cochere.

Man makes plans and the gods laugh, so the saying goes. It was the specific intent of Hopkins' will that Johns Hopkins Medical School be sited on the Clifton estate, which during his lifetime had grown to some 500 acres. Instead, the school trustees bought an existing school building closer to downtown Baltimore. Hopkins also intended that the new university be constructed on the property. The trustees dismissed the site as "malarial" and built the university 2 miles to the northwest. Hopkins had 22 years to spin in his grave while Johns Hopkins University converted his grounds into playing fields and his house into locker rooms. He probably spun faster when, in 1895, the university sold the land to the city of Baltimore for a public park, which it remains today, and turned the house into a sort of land-bound tramp steamer, used by everyone from park police to a municipal golf corporation to an operator of public ballroom dancing. Walls were pulled down, ceilings dropped, mantels and woodwork yanked out and sent to the dump.

The first sign of a new dawn came in December of 1992 when, for a dollar a year, a newly formed non-profit AmeriCorps program called Civic Works rented the house for its headquarters. Civic Works promptly set to work converting trash filled lots into community gardens, mentoring inner city students, rehabilitating abandoned housing, helping people get GEDs, teaching skills to young kids, finding jobs for the unemployed, even raising produce in urban farms. If all this weren't enough, they decided to restore the mansion as well.

Restoration started with one room, but celebration was short-lived when fire broke out in another. Happily, the house did not burn down, and a generous insurance check wound up paying for a new roof.

By 1998, Civic Works was more skilled in getting grants, attracting contributions, cultivating groups like the Friends of Clifton, and getting the estate listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

By 2004, a broad hall running down the east-west spine of the house and a couple of main floor rooms had been restored, purportedly to 1812 appearance. In 2013, however, Civic Works, the Baltimore Parks Department and the Friends of Clifton collaborated on a mega-restoration project that appears to have wiped out much of this previous work. Designed by the Baltimore firm of Gant Brunett Architects, the plan for the mansion amounts to total interior reconstruction. It is informed - indeed, mitigated - by considerable spelunking for historical stencils, wallpapers, etc. buried for generations under cheap paint, dropped ceilings and clumsy wall-boarding.

Clifton is an interesting house, from the standpoint of its structural evolution, the miracle of its survival, and the passion of those involved in its renovation/reconstruction/restoration. Despite the current work-in-progress disarray, I had terrific fun climbing all over it with CW's John Ciekot.

Henry Thompson's Clifton of 1803 was one room deep and occupied the footprint of the present living and breakfast rooms. A kitchen wing would have been appended somewhere on the back. The present main stair, located next to the porte cochere, occupies one of the 1805 wings. When Thompson's 1812 dining room addition replaced the earlier kitchen wing, a new kitchen was installed in the basement underneath it. The current plan is Niernsee's and Nielson's - not inspired, perhaps, but imposing in scale and, when first built, elaborately decorated.

You wouldn't be the first not to notice this frescoed view of the Bay of Naples that ornaments - or ornamented - the wall just inside the front door. Civic Works is absolutely serious in its intention to, one day anyway, restore it.

The long hall running the length of the main floor suggests the architects should have stuck to railroad stations. Its abundant wall space provided opportunity for much painted decoration in the past, and will again the future.

Here's the living room, with a door in the southeast corner that leads out to the porch. In the days before campanile and porte cochere, that door was Captain Thompson's front door. The original Georgian center hall on which it opened was combined by Niernsee and Nielson with the western parlor to make Hopkins' new living room.

Here's the breakfast room, restored in 1994. Outside of it is the long hall, looking west towards the porte cochere. Beyond John is the entrance to a glazed piazza.

Absent being told, I'd have never guessed this was Thompson's octagonal dining room of 1812 - partly, I suppose, because it's not an octagon. The elegant ceiling is barely hanging on; careful demolition has revealed a host of former decorating schemes.

The formerly elegant - and more visually comprehensible - drawing room is a study in Victorian era heft. I wonder who made off with the missing fireplace, unless some bureaucrat from the past simply had it chopped up and thrown out.

The adjoining library, minus what must also have been an imposing mantel, is an equal wreck. The hope is that those exposed fragments of vintage wall treatments will guide future restoration finishes.

The eastern end of the main floor is a forest of new 2 x 4 studs and attached electric cables in which there's not much of a story. Let's return to the main stair from which we'll enter Clifton's most exciting feature, the campanile. Beyond the campanile entrance, located on a landing just short of the second floor hall, a stack of little rooms rises, one on top of the other, ending on a narrow balustraded terrace with sweeping views of all Baltimore.

Clifton hasn't been occupied as a private house since 1873, so there are no bathrooms. Well, that's not quite true; there was one bathroom on the second floor across the hall from the billiard room. Anything that was left got pulled out during installation of a new elevator.

The second floor hall leads to bedrooms in various states of construction - or deconstruction, if you will.

One must step up to the billiard room, due to the extra high ceiling in the drawing room below.

The low steps on the right are outside the billiard room; the blue door on the left is the new elevator; the main stair is at the far end of the hall.

We, however, are taking the back stair for a peek at floor 3, where new studs are enclosing modern HVAC units. A peculiar floor plan once accommodated servants, although how exactly is a mystery to me.

At the foot of the back stair is the original kitchen, barely discernible as such but for an old cooking arm that once held pots in the fireplace. There is nothing peculiar about locating a kitchen on the floor below the dining room. In this case, however, there is no dumbwaiter. Apparently there never was one either. This required servants to hike ridiculous distances back and forth and up and down in order to serve meals in the dining and breakfast rooms above. I cannot fathom what Hopkins' architects were thinking about, since dumbwaiter technology was widespread by the 1850s.

As crucial as anything in the resurection of Clifton is its modern heating plant. 26 geo-thermal wells, each 350' deep, have been drilled around the house to serve 13 zone-controlled heat pumps. I don't really know what that means, but it sounds like they're doing the right thing.

What will Civic Works do with the finished Hopkins mansion? Besides enjoying a new headquarters, they'll invite other non-profits to open shop here, mount history exhibits, run house tours, host weddings, provide a venue for cultural events, and any- and everything else they can think of. It is a grand and ambitious project for which I wish them every success. The link is www.civicworks.com.

Quite and ambitious project. Don't know who has the greater task, these folks or the Aldon Manor crew in Yonkers, NY. Great post

ReplyDeleteexcellent tour! can't wait to see the updated post when the renovations are finished. :-)

ReplyDeleteThis is truly a lovely old home...full of interesting twists and turns.

ReplyDeleteAs for the renovation? Something tells me this is going to cost a pretty penny.

Oh dear! Typo on the vintage postcard at the end of posting. Something tells me Mr. Hopkins was accustomed to such transgressions.

ReplyDeleteWhat a terrific house and kudos to Civic Works for saving it! From the looks of it, it appears to have been on its last legs. What I enjoy so much is that it is a catalogue of styles from the late 18th to mid 19th centuries. The moldings in the breakfast room and what I am guessing is the master bedroom are such beautiful examples of delicate Federalism while the staircase and the ceiling in the drawing room shout out the muscular, in-your-face, voluptuousness of the mid 19th century Victorian. Thanks for sharing yet another gem John!

ReplyDeleteHeck, they are still calling him John to this day. I'd be arrogant about knowing the difference, but I assumed that the name of the university referred to two people! This may be the ultimate fixer-upper. But what a wonderful project. I'm glad the organization has elected to restore, rather than squeeze the remaining life out of it. Thanks for another wonderful post.

ReplyDeleteactually, there's still a Johns Hopkins running around b'more; works with Baltimore Heritage. I've met him; nice guy. :-)

ReplyDelete